How Does a Catholic Get Right with God?

A summary and biblical assessment of the Catholic view of justification

For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.

Romans 3:23-24 (ESV)

There is an old illustration that Christian evangelists used to give, which went something like this:

Imagine that you died tonight and arrived at Heaven’s Gates. As you sheepishly look between the bars, trying to spot a way in, God’s voice thunders from within:

‘Why should I let you into my Heaven?’

It’s a good question. It’s also uncomfortable.

How would you respond?

Any answer worth its salt would include the word ‘because’:

Because I am a good person.

Because you are forgiving.

Because I forgot my keys.

On what grounds should you be allowed into Heaven?

Underlying that question is a quintessential Christian idea:

For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in the body, whether good or evil.

2 Corinthians 5:10 (ESV)

In front of the gates of Heaven, there is a judgement seat. Jesus is sitting on it, and he is going to give you what you deserve.

For some people, this is great news. They know that they are good people. For others, this is not such great news - they know that they’re not.

But by what standard will Jesus judge what is ‘good or evil’?

For whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become accountable for all of it. For he who said, “Do not commit adultery,” also said, “Do not murder.” If you do not commit adultery but do murder, you have become a transgressor of the law.

James 2:10-11 (ESV)

Uh oh.

Jesus is going to judge people using God’s law. And he’s going to be one of those super strict teachers - get question 217 wrong and you fail the whole exam.

But maybe God’s laws aren’t too hard to follow. Maybe he just wants us to be good citizens - like make sure you recycle and pay your taxes.

Unfortunately, Jesus uses a higher standard than Greenpeace:

You have heard that it was said to those of old, ‘You shall not murder; and whoever murders will be liable to judgment.’ But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment; whoever insults his brother will be liable to the council; and whoever says, ‘You fool!’ will be liable to the hell of fire.

Matthew 5:21-22 (ESV)

Double uh oh.

At this point, the Christian view puts people (as my Swiss friend liked to say), in a pickle:

To get to Heaven you have to be right with God.

To be right with God, you have to obey everything he has ever said, without exception.

There was that one time I insulted my brother for being such an idiot.1

And yet, after the Apostle John visits Heaven, he writes about it, saying:

After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands.

Revelation 7:9 (ESV)

How did they all get there?

Or rather, how did they all get right with God, in order to get there?

Roman Catholicism has an answer.

In this article, I am going to give a summary of that answer. And then I will assess it in the context of what the Bible says.

Official Catholic Teachings

How can you summarise what the Roman Catholic church believes about something?

Again, they have an answer:

All those things are to be believed with divine and Catholic faith which are contained in the Word of God, written or handed down, and which the Church, either by a solemn judgment, or by her ordinary and universal magisterium, proposes for belief as having been divinely revealed.

First Vatican Council, 244-2452

Who is the magisterium? The Catholic Catechism defines it as ‘the Pope’ and ‘the college of bishops in communion with Him’.3 More specifically:

Although the bishops, taken individually, do not enjoy the privilege of infallibility, they do, however, proclaim infallibly the doctrine of Christ on the following conditions: namely, when, even though dispersed throughout the world but preserving for all that amongst themselves and with Peter's successor the bond of communion, in their authoritative teaching concerning matters of faith or morals, they are in agreement that a particular teaching is to be held definitively and absolutely.

Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium4

What does this mean? When all the Catholic bishops formally agree with the Pope on a given teaching, that teaching becomes the official Catholic position.5

More specifically, that teaching is then seen as infallible - it is not possible for it to be wrong.6

But where can we find those teachings? As Catholic Canon Law says:

The college of bishops also possesses infallibility in teaching when the bishops gathered together in an ecumenical council exercise the magisterium as teachers and judges of faith and morals who declare for the universal Church that a doctrine of faith or morals is to be held definitively;

Code of Canon Law, can. 749 §2 (emphasis added)7

So in summary: we can find the official and definitive Catholic teaching about something in the documents produced by their Ecumenical Councils.8

What are those Ecumenical Councils? The three most recent ones have been:

The Council of Trent (1545)

The First Vatican Council (1869)

The Second Vatican Council (1962)

The Catholic View of Justification

So let’s dive in. What do the councils of the Catholic church have to say about our question:

How does a Catholic get right with God?

The Council of Trent starts by acknowledging that everyone is born in a state of not being right with God:

All men had lost their innocence in the prevarication of Adam - having become unclean, and, as the apostle says, by nature children of wrath.

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Chapter I9

This resonates with the biblical texts we saw earlier - everyone is under judgement (wrath) for not obeying God’s law (sin). Those ‘sins’ cause us to be ‘alienated from God’ (Ibid, Chapter V).

Moreover, everyone is born in this state because everyone is a descendent of the first man Adam:

For as in truth men, if they were not born propagated of the seed of Adam, would not be born unjust, - seeing that, by that propagation, they contract through him, when they are conceived, injustice as their own.

Ibid, Chapter III

Here we see the key problem: everyone is born unjust and has his own injustice.

What does that mean?

It can be hard to understand until we dig into the original Latin term that the council is using here:

justitia (noun)

equality

justice

righteousness10

The term justice is being used in its third sense, namely righteousness.11

So, in other words, the Catholic view is that each person is born with their own unrighteousness. And that unrighteousness is the reason they are not right with (alienated from) God.

So how can someone get right with God then?

Logically, by replacing their unrighteousness with righteousness:

By which words, a description of the Justification of the impious is indicated, - as being a translation, from that state wherein man is born a child of the first Adam, to the state of grace

Ibid, Chapter IV

So, if they were not born again in Christ, they never would be justified; seeing that, in that new birth, there is bestowed upon them, through the merit of His passion, the grace whereby they are made just.

Ibid, Chapter III

Here we see a parallel: just like you were given unrighteousness (injustice) in your first birth, you are given righteousness (justice) in a new birth.

But what does it mean to receive ‘righteousness’? Is it like getting a gift that you hold onto? Or does it go deeper than that?

Justification itself, which is not remission of sins merely, but also the sanctification and renewal of the inward man, through the voluntary reception of the grace, and of the gifts, whereby man of unjust becomes just

Ibid, Chapter VII

When someone receives that righteousness, it actually becomes part of his ‘inward man’ - part of his very nature.

And so, is that it? Do you just need to receive righteousness by being born again in Christ?

Well, you can actually lose that righteousness. Specifically when you commit a serious (mortal) sin:

It is to be maintained, that the received grace of Justification is lost, not only by infidelity whereby even faith itself is lost, but also by any other mortal sin whatever, though faith be not lost

Ibid, Chapter XV

And you can regain it:

As regards those who, by sin, have fallen from the received grace of Justification, they may be again justified, when, God exciting them, through the sacrament of Penance they shall have attained to the recovery, by the merit of Christ, of the grace lost

Ibid, Chapter XIV

Equally, that righteousness increases when you do good works:

They, through the observance of the commandments of God and of the Church, faith co-operating with good works, increase in that justice which they have received through the grace of Christ, and are still further justified

Ibid, Chapter X

Finally, by combining the righteousness received from God and the righteousness gained by good works, someone can merit eternal life:

Life eternal is to be proposed to those working well unto the end, and hoping in God, both as a grace mercifully promised to the sons of God through Jesus Christ, and as a reward which is according to the promise of God Himself, to be faithfully rendered to their good works and merits.

Ibid, Chapter XVI (emphasis added)

In summary then, according to official Catholic teaching, by combining the righteousness given in Christ, with the righteousness gained from good works, someone becomes internally righteous - and that will make him right with God.

The Catholic View of the Means of Justification

Yet there is something missing from the summary above. How do you receive that righteousness? And how do those good works happen?

With regards to receiving righteousness:

The beginning of the said Justification is to be derived from the prevenient grace of God, through Jesus Christ, that is to say, from His vocation, whereby, without any merits existing on their parts, they are called; that so they, who by sins were alienated from God, may be disposed through His quickening and assisting grace, to convert themselves to their own justification, by freely assenting to and co-operating with that said grace

Ibid, Chapter V

First God makes someone ‘disposed’ to ‘convert themselves’ by ‘quickening’ and ‘assisting’ their wills by an act of ‘grace’. Then, based on this initial assistance, a man can convert by ‘freely assenting’ to and ‘co-operating with’ God’s initiative.12

This assent to God’s initiative happens through ‘faith’:

Now they (adults) are disposed unto the said justice, when, excited and assisted by divine grace, conceiving faith by hearing, they are freely moved towards God, believing those things to be true which God has revealed and promised

Ibid, Chapter VI

And so, receiving righteousness happens internally?

Not entirely. In order for someone to accept God’s righteousness, their response needs to be enacted physically by carrying out the sacraments of penance and baptism:

By that penitence which must be performed before baptism

Ibid, Chapter VI

The instrumental cause is the sacrament of baptism, which is the sacrament of faith

Ibid, Chapter VII

On the other hand, how do those good works happen?

They were so far the servants of sin, and under the power of the devil and of death, that not the Gentiles only by the force of nature, but not even the Jews by the very letter itself of the law of Moses, were able to be liberated, or to arise, therefrom although free will, attenuated as it was in its powers, and bent down, was by no means extinguished in them.

Ibid, Chapter I

Although everyone still has a (weakened) ‘free will’, no one can be ‘liberated’ from ‘sin’ just by their own ‘force of nature’.

However, after the ‘new birth’:

The charity of God is poured forth, by the Holy Spirit, in the hearts of those that are justified, and is inherent therein: whence, man, through Jesus Christ, in whom he is ingrafted, receives, in the said justification, together with the remission of sins, all these (gifts) infused at once, faith, hope, and charity.

Ibid, Chapter VII

God gives the ‘gifts’ of ‘faith, hope, and charity’ so that they become ‘infused’ and ‘inherent’ in the person who receives them. However, someone can still refuse these free gifts, and so their reception depends on his co-operation (see above on losing God’s righteousness):

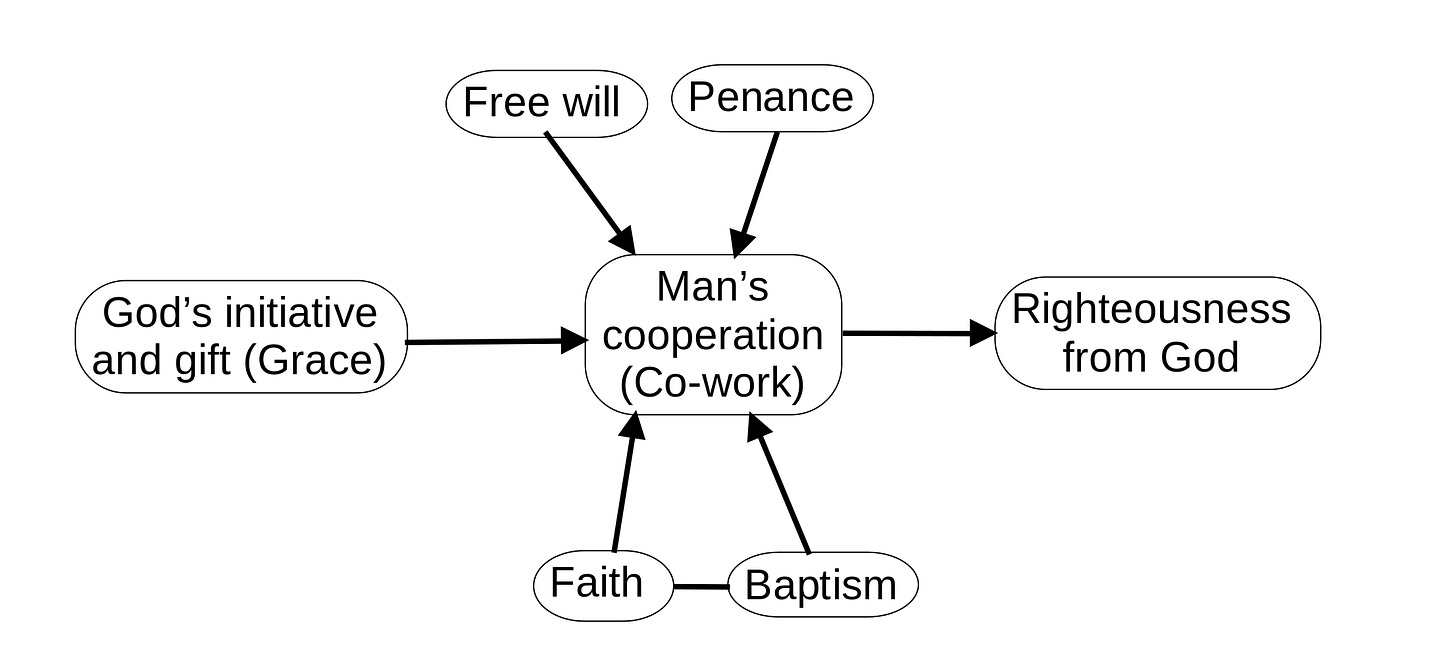

Overall Diagram of the Catholic View of Justification

And so, we can summarise everything we said above in a single diagram:13

As can be seen, there are many Christian terms used in the Catholic view (faith, righteousness, justification, baptism), however their full meaning can only be grasped in the context of the overall Catholic system.

Grace is present, and yet its role is always dependent on man’s cooperation. Being right with God is also present, but is entirely dependent on inherent righteous. Faith is there, however it is inextricably linked to the physical act of baptism.

Biblical View of Justification

As I mentioned above, the Catholic ecumenical councils provide us with the official Catholic view on justification.

And yet, in our quote from the First Vatican Council (see above), Catholicism claims that its views come (in part) from the ‘written’ ‘Word of God’. In other words, Catholicism claims to inherit the Bible’s teachings.14

Which leads us to a natural question: Are the views summarised above found in the Bible?

A good place to start would be the word justification itself. As mentioned above, the word justification comes from the Latin word justitia, which means righteousness. However, justitia is itself a translation15 of the biblical Greek term dikaiosunē:

dikaiosunē 'righteousness' (G1343)

righteousness, what is right, justice, the act of doing what is in agreement with God’s standards, the state of being in proper relationship with God16

Here, we find some nuances compared to the Catholic definition of justice/righteousness. Specifically, righteousness is not just an ‘internal’ state, but it can also be an external ‘state of being in proper relationship with God’.

If we go further and focus on the Greek term for justify, we find:

dikaioō 'to justify' (G1344)

to justify, vindicate, declare righteous, to put someone in a proper relationship with another, usually referring to God’s relationship to humankind, implying a proper legal or moral relationship17

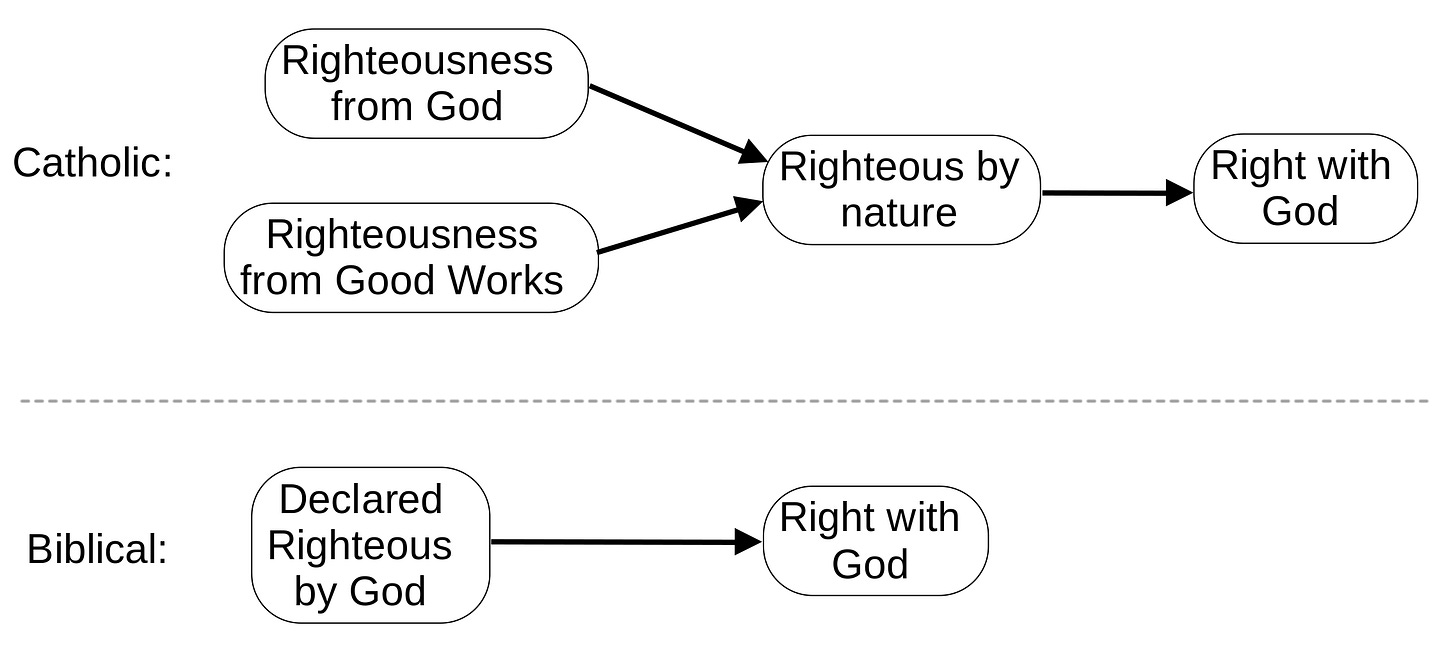

This provides us with a meaning for ‘justify’ that is completely absent from the Catholic view. As summarised in the diagram above, the Catholic view is that God consistently justifies someone internally. The person naturally (or inherently) becomes righteous.

However, in the definition above, we find another possible meaning: to ‘declare righteous’. More specifically, we find that ‘justify’ can refer to being ‘put’ in a ‘proper relationship’ with God.

Where do these other meanings come from?

For if Abraham was justified by works, he has something to boast about, but not before God. For what does the Scripture say? “Abraham believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness.” Now to the one who works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due. And to the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness, just as David also speaks of the blessing of the one to whom God counts righteousness apart from works:

“Blessed are those whose lawless deeds are forgiven,

and whose sins are covered;

blessed is the man against whom the Lord will not count his sin.”Romans 4:2-8 (ESV) (emphasis added)

In this passage, Paul contrasts two types of becoming righteous (justification):18

Righteous by Works: When someone ‘works’, his ‘wages’ are his ‘due’. And so someone who is righteous by (good) works deserves his right standing with God.

Counted Righteous by Faith: When someone ‘believes’ God, ‘his faith is counted as righteousness’. This righteousness is a ‘gift’.

The key term that appears here is counted:

logizomai 'to count' (G3049)

to credit, count, reckon; regard, think, consider19

The righteousness (justification) that Paul talks about here is external to the person who has faith. The person himself is not internally righteous, but is ‘regarded’ or ‘considered’ (counted) righteous.

Another way to say this is that a person is ‘declared’ righteous by God:

Biblical View of the Means of Justification

How then is someone counted righteous (externally justified) according to the Bible?

But now the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from the law, although the Law and the Prophets bear witness to it— the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe. For there is no distinction: for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith. This was to show God's righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins. It was to show his righteousness at the present time, so that he might be just and the justifier of the one who has faith in Jesus.

Romans 3:21-26 (ESV) (emphasis added)

The key word repeated in this passage is faith or believe:

pistis ‘faith/trust’ (G4102)

faith, faithfulness, belief, trust, with an implication that actions based on that trust may follow; “the faith” often refers to the Christian system of belief and lifestyle20

The term pistis contains within it both knowledge and trust. And so, someone receives God’s external righteousness by knowing and trusting that God has declared him righteous:

Meanwhile, the passage also gives us the fundamental reason that someone is declared righteous: the ‘propitiation’ of ‘Jesus Christ’:

hilastērios ‘propitiation’ (G2435)

atoning sacrifice; atonement cover, the place where sins are forgiven; traditionally propitiation or mercy seat

The ‘sacrifice’ of Jesus ‘atones’ for sins - therefore, the death of Christ pays for the external righteousness received by a believer:

Finally, it is important to note that God’s declaration that someone is righteous is both complete and final from the moment it is made:

But when Christ had offered for all time a single sacrifice for sins, he sat down at the right hand of God, waiting from that time until his enemies should be made a footstool for his feet. For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified.

And the Holy Spirit also bears witness to us; for after saying,

“This is the covenant that I will make with them

after those days, declares the Lord:

I will put my laws on their hearts,

and write them on their minds,”then he adds,

“I will remember their sins and their lawless deeds no more.”

Where there is forgiveness of these, there is no longer any offering for sin.

Hebrews 10:12-18 (ESV) (emphasis added)

This passage ties together the ‘single sacrifice for sins’ made by Christ, and the definitive ‘forgiveness’ of ‘sins’ so that Christ ‘has perfected for all time’ those who believe. The term ‘perfected’ (teleioō) means to ‘complete, finish’21 and is in the perfect indicative active22 form, which refers to a ‘completed action in the present time’.23

Therefore, the forgiveness of sins has already, completely and definitively been accomplished for those who are justified by faith.

This is why Paul can say:

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.

Romans 8:1 (ESV) (emphasis added)

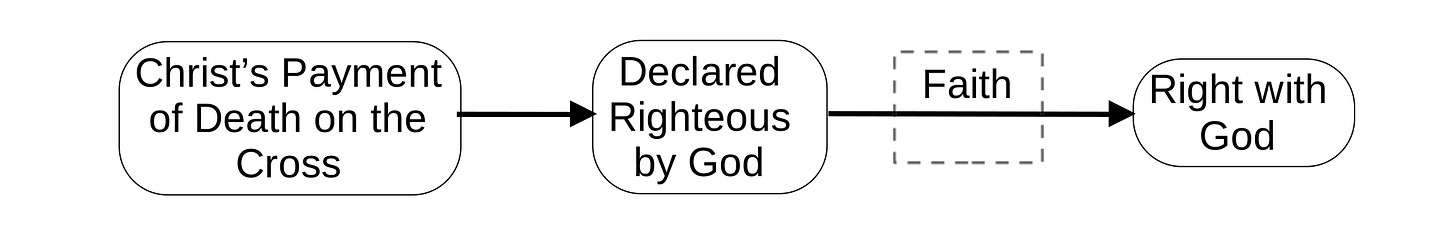

Overall Diagram of the Biblical View of Justification

Therefore, we can now represent the biblical view of (external) justification as:

It is important to note the emphasis of this diagram: the emphasis of every box is external. More specifically, ever part of the diagram has a God-centred focus:

Christ’s payment on the Cross is accomplished entirely and exclusively by Christ.

The declaration of righteousness is made entirely and sovereignly by God.

Faith is fundamentally a state of trusting in the (external) works of God.

Being right with God is seen as the (external and objective) state of one’s relationship with God.

Comparison of Views on Justification

Now that we have summarised both the Catholic and biblical views, it would be worthwhile to compare and contrast them.

Beginning with each view of justification, it is interesting to note that the Catholic view (being justified via internal righteousness) is actually referred to in the Bible:

For all who have sinned without the law will also perish without the law, and all who have sinned under the law will be judged by the law. For it is not the hearers of the law who are righteous before God, but the doers of the law who will be justified.

Romans 2:12-13 (ESV) (emphasis added)

Here, the stated ‘doers’ of the law attain an internal righteousness by which they might be justified.

However, attaining justification this way is considered impossible by Paul:

For all who rely on works of the law are under a curse; for it is written, “Cursed be everyone who does not abide by all things written in the Book of the Law, and do them.” Now it is evident that no one is justified before God by the law, for “The righteous shall live by faith.” But the law is not of faith, rather “The one who does them shall live by them.”

Galatians 3:10-12 (ESV) (emphasis added)

If someone relies on an internal righteousness (derived from works), then they are under a ‘curse’ since they would need to ‘abide by all things written in the Book of the Law’.

Therefore, ‘no one is justified before God by the law’.

This means that using internal ‘righteousness from good works’ as a basis for justification is both identified and condemned by the Bible.24

However, being justified by good works was only one of the two aspects of being justified from a Catholic perspective (see diagram above). What about gaining ‘righteousness from God’? Specifically, what if the ‘righteousness from God’ in the Catholic view is actually the same thing as being ‘declared righteous by God’ in the biblical view?

In fact, the Council of Trent clarified their position on this issue:

If any one saith, that men are justified, either by the sole imputation of the justice of Christ, or by the sole remission of sins, to the exclusion of the grace and the charity which is poured forth in their hearts by the Holy Ghost, and is inherent in them; or even that the grace, whereby we are justified, is only the favour of God; let him be anathema.

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Canon XI25 (emphasis added)

Here, the council identifies ‘sole imputation’ (counting) of ‘justice’ (righteousness) as contrary to their views. Instead, the ‘righteousness from God’ must inviolably have an ‘inherent’ aspect that is ‘poured forth’ into the ‘hearts’ of the justified.

In order to display the importance and strength of this position, Canon XII declares an ‘anathema’ on anyone who disagrees. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

At a late period, Gregory IX (1227-41), bk. V, tit. xxxix, ch. lix, Si quem, distinguishes minor excommunication, or that implying exclusion only from the sacraments, from major excommunication, implying exclusion from the society of the faithful. He declares that it is major excommunication which is meant in all texts in which mention is made of excommunication. Since that time there has been no difference between major excommunication and anathema, except the greater or less degree of ceremony in pronouncing the sentence of excommunication.

Anathema remains a major excommunication which is to be promulgated with great solemnity.

Hence, the ‘anathema’ pronounced at the time of the Council of Trent (1547) corresponds to a ‘major excommunication’ from the Catholic Church.

Meanwhile, according to the biblical view, being ‘declared righteous by God’ is an entirely external act that changes only God’s ‘regard’ (counting) of a believer - and not the internal state of that believer, in any way.26

Believing in the biblical view of justification therefore entails excommunication from the Catholic Church.27

Comparison of Views on the Means of Justification

Seeing then that the Catholic and biblical views of justification are at odds, what about their respective views of how justification takes place?

While there are many elements in the Catholic view regarding the means of justification, they all pass through a single entity: man’s cooperation.

As was mentioned in a previous footnote, ‘cooperation’ refers the the Latin term cooperando which literally means ‘co-work’. Hence, there are many actions (works) that take place as a part of man’s cooperation with God’s grace, including baptism and penance. Faith plays a role, but it is subordinate to and an expression of man’s ‘co-work’ with God.

Meanwhile, in the biblical view, ‘faith’ is consistently seen as opposed and contradictory to ‘work’:

We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified.

Galatians 2:15-16 (ESV) (emphasis added)

The word not (ou) is repeated in this passage three times, making Paul’s point absolutely clear: works do ‘not’ justify. Rather, we are justified through faith.

More specifically, Paul states that adding works (in this case circumcision28) to one’s justification actually annuls that justification:

Look: I, Paul, say to you that if you accept circumcision, Christ will be of no advantage to you. I testify again to every man who accepts circumcision that he is obligated to keep the whole law. You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law; you have fallen away from grace.

Galatians 5:2-4 (ESV) (emphasis added)

According to the Bible, justification by faith is not only necessary, but exclusive. If anything else is added to justification by faith, then it ‘will be of no advantage to you’ and you will have ‘fallen away from grace’, being ‘severed from Christ’.

And while the biblical statements here are strong and exclusive, the Council of Trent made equally strong and exclusive statements concerning its own view:

If any one saith, that justifying faith is nothing else but confidence in the divine mercy which remits sins for Christ's sake; or, that this confidence alone is that whereby we are justified; let him be anathema.

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Canon XII (emphasis added)

If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema.

Ibid, Canon IX (emphasis added)

Again, we find an ‘anathema’ (major excommunication) applied to anyone who believes the biblical view that faith alone justifies.

And so we find diametrically opposed anathemas being mutually applied between the biblical and Catholic views of the means of justification.

The last means of justification to consider is the ‘grounds’ of justification. Essentially, by which merits is someone justified?

The Bible repeatedly refers to the grounds of justification as having been completed and accomplished, once for all, by Christ’s work on the Cross:

And every priest stands daily at his service, offering repeatedly the same sacrifices, which can never take away sins. But when Christ had offered for all time a single sacrifice for sins, he sat down at the right hand of God, waiting from that time until his enemies should be made a footstool for his feet. For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified.

Hebrews 10:11-14 (ESV) (emphasis added)

When Jesus had received the sour wine, he said, “It is finished,” and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.

John 19:30 (ESV)

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.

Romans 8:1 (ESV) (emphasis added)

Meanwhile, in the Catholic view, we find a continually growing justification based on the merits of the good works performed by the believer:

If any one saith, that the justice received is not preserved and also increased before God through good works; but that the said works are merely the fruits and signs of Justification obtained, but not a cause of the increase thereof; let him be anathema.

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Canon XXIV (emphasis added)

‘Good works’ ‘cause’ an ‘increase’ in one’s ‘justice’ (righteousness) and therefore ‘justification’.

Again, the council pronounced an ‘anathema’ (major excommunication) on anyone who disagrees with its view on the grounds of justification. In this situation, that includes those who hold the biblical view of those grounds.

Conclusion

Looking back at our original question:

How does a Catholic get right with God?

We could provide the following answer:

A Catholic gets right with God by increasing his internal righteousness. He does this by receiving righteousness from God and gaining righteousness from good works. However, in both these cases the man cooperates (co-works) with God to increase his internal righteousness.

This answer is grounded in the official Catholic documents produced (primarily) at the Council of Trent (1545). Since the Catholic Church sees the decrees of its ecumenical councils as being infallible, we can be confident that the views expressed in those documents are the definitive and final Catholic views on justification.

However, when we compare the Catholic view of justification with the Bible, we find some key differences:

Declared (external) righteousness is entirely missing from the Catholic view, while being the foundation of the biblical view of justification.

‘Righteousness by faith’ and ‘righteousness by works’ are clearly portrayed as contradictory and mutually exclusive in the biblical view. Meanwhile, the Catholic view not only sees them as compatible, but as conjoined in the process of justification.

Justification in the biblical view is an objective act carried out by God alone and then applied to the believer, via his faith. Meanwhile, the Catholic view makes justification dependent on the (subjective) cooperation (co-work) of the believer with God.

Justification in the biblical view is final and complete at the very moment God declares it. Meanwhile, justification in the Catholic view can be gained, lost, regained, increased and decreased over time according to the actions of the believer.

The Catholic church has pronounced anathemas (excommunication) against anyone who disagrees with its position on the above points. These anathemas are seen as infallible and therefore cannot be revoked by the Catholic church.

From the above considerations, I conclude that the official Catholic view of justification is fundamentally and definitively incompatible with the biblical view of justification.

And so, coming back to our first question: How did all the people in Revelation 7:9 get into Heaven? John records the answer in the verses which follow:

Then one of the elders addressed me, saying, “Who are these, clothed in white robes, and from where have they come?” I said to him, “Sir, you know.” And he said to me, “These are the ones coming out of the great tribulation. They have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.”

Revelation 7:13-14 (ESV)

How can all of these people stand before a Holy God who judges the slightest sin?

All of them are wearing ‘white robes’ - perfect, moral righteousness.

And how did their robes become white? They ‘made them white in the blood of the Lamb’.

These robes of righteousness cover them with the finished work of Jesus on the Cross, where he paid for all of their sins.

Hence their righteousness is not internal, but external. Not something in them but something on them. It is not a result of their good works, but a result of Christ’s good work on the Cross. And so their confidence before God does not come from their past co-work with God’s grace. Rather it comes from the complete payment for sin that Jesus made on the Cross, once and for all.

May we all put on those perfect robes of righteousness, so that our own filthiness might be covered, and we might stand before God in perfect confidence when we arrive at his gates:

Now Joshua was standing before the angel, clothed with filthy garments. And the angel said to those who were standing before him, “Remove the filthy garments from him.” And to him he said, “Behold, I have taken your iniquity away from you, and I will clothe you with pure vestments.”

Zechariah 3:3-4 (ESV)

Thoughtful Reformed

Appendix

The Second Vatican Council and Justification

While the clearest and most definitive Catholic statements concerning justification are found in the documents produced by the Council of Trent, there have been two Catholic ecumenical councils since then.

While neither of those councils addressed justification to a significant degree, the Second Vatican Council represented a shift in Catholic theology which has implications for their view of justification:

Finally, those who have not yet received the Gospel are related in various ways to the people of God.(18*) In the first place we must recall the people to whom the testament and the promises were given and from whom Christ was born according to the flesh.(125) On account of their fathers this people remains most dear to God, for God does not repent of the gifts He makes nor of the calls He issues.(126) But the plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator. In the first place amongst these there are the Muslims, who, professing to hold the faith of Abraham, along with us adore the one and merciful God, who on the last day will judge mankind. Nor is God far distant from those who in shadows and images seek the unknown God, for it is He who gives to all men life and breath and all things,(127) and as Saviour wills that all men be saved.(128) Those also can attain to salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, yet sincerely seek God and moved by grace strive by their deeds to do His will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience.(19*) Nor does Divine Providence deny the helps necessary for salvation to those who, without blame on their part, have not yet arrived at an explicit knowledge of God and with His grace strive to live a good life. Whatever good or truth is found amongst them is looked upon by the Church as a preparation for the Gospel.(20*)

The Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium 1629

Here, we find a shift in language from the definitive, either-or statements made at the Council of Trent. The ‘plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator’, including:

The Jewish people who ‘remains most dear to God’

The ‘Muslims’ who ‘along with us adore the one and merciful God’

Those who follow ‘shadows and images’ of the ‘unknown God’

Specifically:

Those also can attain to salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, yet sincerely seek God and moved by grace strive by their deeds to do His will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience.

Ibid

The council focusses on those who ‘do not know’ about Jesus and the Catholic church. For these peoples, if they ‘sincerely seek’ God via the ‘dictates of conscience’ they ‘can attain to salvation’.

How do the above statements fit with the Council of Trent?

There is a strong case to be made that the two are mutually incompatible, especially when focussing on the original intent of the Council of Trent. While those who do not have an ‘explicit knowledge of God’ are not specifically referenced in the Sixth Session, its scope is both universal and unqualified:

If any one saith, that man may be justified before God by his own works, whether done through the teaching of human nature, or that of the law, without the grace of God through Jesus Christ; let him be anathema.

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Canon I (emphasis added)

Here the ‘teaching of human nature’ includes the content of a man’s natural ‘conscience’. Equally, ‘grace’ is communicated necessarily through the physical act of a Catholic baptism:

Of this Justification the causes are these: … the instrumental cause is the sacrament of baptism, which is the sacrament of faith, without which (faith) no man was ever justified;

Ibid, Chapter VII (emphasis added)

One way to try to reconcile Lumen Gentium 16 with the Council of Trent is to say that God’s ‘grace’ can be given to someone without their knowledge or awareness of it:

… moved by grace strive by their deeds to do His will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience.

The Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium 16

And yet the Council of Trent uses the precise language of being ‘moved towards God’ only in the context of ‘hearing’ and ‘believing’ what God has ‘revealed’ about the ‘redemption that is in Christ Jesus’:

Now they (adults) are disposed unto the said justice, when, excited and assisted by divine grace, conceiving faith by hearing, they are freely moved towards God, believing those things to be true which God has revealed and promised, - and this especially, that God justifies the impious by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus;

The Council of Trent, The Sixth Session, Chapter VI (emphasis added)

Beyond these serious tensions, Lumen Gentium cannot be applied to anyone currently reading this article.

If you have read this article then you have read the Catholic understanding of the Gospel and so cannot claim that you ‘do not know the [Catholic] Gospel of Christ or His Church’.

Thus I would suggest that the Second Vatican Council introduces, at best, unclear tensions with the Council of Trent that do not apply to those who have been exposed to Catholic teaching.

Therefore, the clear and unambiguous teachings found in the Council of Trent concerning justification are to be preferred for summarising the official Catholic understanding of justification.

The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification

In 1999 the Catholic Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and the Lutheran World Federation produced a document called the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification.

The document begins by acknowledging mutual condemnation between the Catholic and Lutheran churches at the time of the Reformation concerning the doctrine of justification:

Doctrinal condemnations were put forward both in the Lutheran Confessions and by the Roman Catholic Church’s Council of Trent. These condemnations are still valid today and thus have a church-dividing effect.

The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, 130

However, the document goes on to state that the Catholic and Lutheran churches have reached a ‘common understanding’ of justification such that the ‘remaining differences are no longer the occasion for doctrinal condemnations’:

The present Joint Declaration has this intention: namely, to show that on the basis of their dialogue the subscribing Lutheran churches and the Roman Catholic Church are now able to articulate a common understanding of our justification by God’s grace through faith in Christ. It does not cover all that either church teaches about justification; it does encompass a consensus on basic truths of the doctrine of justification and shows that the remaining differences in its explication are no longer the occasion for doctrinal condemnations.

Ibid, 5 (emphasis added)

How does the document claim to do this?

In their respective histories our churches have come to new insights. Developments have taken place which not only make possible, but also require the churches to examine the divisive questions and condemnations and see them in a new light.

Ibid, 7 (emphasis added)

It is important to note that the Lutheran churches are descendants of Martin Luther’s theology, which corresponds in large part to the biblical view of justification outlined in this article.

And so does this document manage to reconcile the mutually incompatible Catholic and biblical views of justification by ‘new insights’?

By way of example, here is how the document seeks to reconcile the Lutheran and Catholic understandings of being declared righteous:

We confess together that God forgives sin by grace and at the same time frees human beings from sin’s enslaving power and imparts the gift of new life in Christ. When persons come by faith to share in Christ, God no longer imputes to them their sin and through the Holy Spirit effects in them an active love. These two aspects of God’s gracious action are not to be separated, for persons are by faith united with Christ, who in his person is our righteousness (1 Cor 1:30): both the forgiveness of sin and the saving presence of God himself. Because Catholics and Lutherans confess this together, it is true to say that:

Ibid, 22 (emphasis added)

So far, there is nothing written that was not already present in the Council of Trent. Paragraph 22 talks about being ‘born again’ by God’s ‘gracious action’ by ‘faith’ for the ‘forgiveness of sin’.

After this, we see how the question of declared righteousness is handled by the Lutheran and Catholic sides:

When Lutherans emphasize that the righteousness of Christ is our righteousness, their intention is above all to insist that the sinner is granted righteousness before God in Christ through the declaration of forgiveness and that only in union with Christ is one’s life renewed. When they stress that God’s grace is forgiving love (“the favor of God”), they do not thereby deny the renewal of the Christian’s life. They intend rather to express that justification remains free from human cooperation and is not dependent on the life-renewing effects of grace in human beings.

Ibid, 23 (emphasis added)

The Lutheran position remains unchanged: ‘righteousness’ comes from a ‘declaration of forgiveness’ which is ‘free from cooperation’ and does not ‘depend’ on any goodness in the human being justified.

When Catholics emphasize the renewal of the interior person through the reception of grace imparted as a gift to the believer, they wish to insist that God’s forgiving grace always brings with it a gift of new life, which in the Holy Spirit becomes effective in active love. They do not thereby deny that God’s gift of grace in justification remains independent of human cooperation. [cf. Sources for section 4.2].

Ibid, 24 (emphasis added)

Meanwhile, the Catholic view remains the same. Only the initial ‘grace’ of God is ‘independent of human cooperation’ as a ‘gift of new life’.

So what has changed?

The first change is the addition of the term ‘emphasizes’. Instead of portraying the two positions as being substantially different, their difference is reduced to an ‘emphasis’.

Meanwhile, there are significant omissions: the Catholic view does not address the ‘declared forgiveness’ in the Lutheran view. It also does not address the lack of human cooperation in justification according to the Lutheran view (remember the difference between God’s initial ‘grace’ and actual ‘justification’ in the Catholic view).

The two views speak past each other, while all differences are attributed to different emphases.

And so the ‘common understanding’ proposed is not a resolution of differences, but rather a statement that those differences do not truly matter.

I am afraid that this is an unfair treatment of both the historic Lutheran and Catholic views.

The entire crux of the disagreement was precisely over such issues as ‘declared righteousness’ and ‘human cooperation’ in justification.

The Lutherans and Catholics understood each other only too well.

And so by stating that these difference are not significant, the document does not actually fulfil its initial claim to maintain that the original ‘condemnations are still valid today and thus have a church-dividing effect.’

In fact, the project undertaken in this joint declaration is not possible because there is a logical contradiction between the Lutheran and Catholic positions. Both cannot be held simultaneously to be true.

And so, by seeking to reconcile the two views without actually denying any of the specific content present in either view, the document is unable to effect any resolution.

At best it is able to reproduce instances of ‘talking past’ one another.

At worst, it actually disregards the content of both views.

Therefore, the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification does not present any significant modifications to the inherent opposition between the biblical and Catholic views of justification presented in this article.

OK. Maybe there were those two times I did that.

You will note a certain kind of circularity in this claim by the Catholic Church. The claim that decisions by the council of bishops are infallible was made by a decision of the council of bishops. Such circularity is actually innate to anything which claims ultimate authority. To which authority figure could an ultimate authority appeal to, apart from itself?

It is worth noting that the Pope is also able to formally declare a teaching as infallible: ‘… the Roman Pontiff, when he speaks ex cathedra, that is, when in discharge of the office of pastor and teacher of all Christians, by virtue of his Apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine regarding faith or morals to be held by the Universal Church is, by the divine assistance promised to him in Blessed Peter, possessed of that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer willed that his Church should be endowed in defining doctrine regarding faith or morals; and that , therefore, such definitions of the Roman Pontiff are of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, irreformable.’ (First Vatican Council, Pastor Aeturnus)

There is one loophole in this statement that I could think of: as far as I know, Catholic Canon Law is not infallible. So you could argue that some ecumenical councils do not qualify as moments where the bishops are ‘in agreement that a particular teaching is to be held definitively and absolutely’ (Lumen Gentium). However, the documents published by each council identify themselves as being a product of formal agreement between all the bishops. See for example the beginning of the Sixth Session of the Council of Trent: https://history.hanover.edu/texts/trent/ct06.html

The term righteousness itself needs to be defined. In a biblical context, justitia was Jerome’s translation of the Greek work dikaiosunē which is defined as ‘righteousness, what is right, justice, the act of doing what is in agreement with God’s standards, the state of being in proper relationship with God’ (STEP Bible)

It is important to note that the Latin term translated as ‘co-operating’ is cooperando which literally means to ‘work together with’ (Wiktionary). So, in a significant way, the Catholic view is that a man ‘works with’ God to accept his righteousness.

Note the extra box pointing to man’s cooperation. There are in fact additional ways to increase internal righteousness in the Catholic system, for example practising the other sacraments: ‘If any one saith, that the sacraments of the New Law are not necessary unto salvation, but superfluous; and that, without them, or without the desire thereof, men obtain of God, through faith alone, the grace of justification; – though all (the sacraments) are not necessary for every individual; let him be anathema’ (The Council of Trent, The Seventh Session, Canon IV)

Vatican I also refers to the ‘Word of God’ that has been ‘handed down’ via Catholic tradition.

Specifically in the Latin Vulgate, a translation of the Bible by Jerome (382 AD). The Vulgate was the primary version of the Bible in Roman Catholicism until the publication of Divino afflante Spiritu by Pope Pius XII in 1943.

Remember that the words ‘justified’, ‘justification’ and ‘righteous’ are all translations of the same underlying Greek base term dikaio (see STEP).

Why then does Paul speak about internal righteousness that could be attained through (perfect) good works? In context, Romans 2:12-13 is written to Jews who believed they could attain such righteousness. And indeed, if someone could perfectly follow God’s law in every respect, they could claim that obedience as the basis of their right standing with God. Yet, due to Adam’s sin, no one could ever claim that (see Romans 5:12), save the one man who never sinned - Jesus Christ.

This means that the rejection of the word ‘sole’ in Canon XII does indeed put it in opposition to the biblical view.

This is indeed what would take place during the time of the Reformation when the Council of Trent was convened.

Some might argue that Paul is only opposing works done according to the Law of Moses. And yet, the entire argument made by Paul in Romans is that both Jews and non-Jews are under condemnation because they do not obey God’s universal moral law (see Romans 2:12). The Jewish law merely exacerbates the situation since it gives greater knowledge of, and therefore accountability for, God’s universal moral law (see Romans 3:19-20, Romans 7:7-12).